Cannabis: The Elixer of Champions!

Former

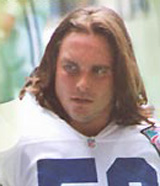

Cowboy Mark Stepnoski tackles new role -- leading the charge

for marijuana reform!

Former

Cowboy Mark Stepnoski tackles new role -- leading the charge

for marijuana reform!

Dallas Observer, October 31, 2002

URL: http://dallasobserver.com/issues/2002-10-31/news.html/1/index.html

BY MARK DONALD

He knows it won't be easy--coming out of the "smoky closet," as one marijuana advocate puts it. After all, he has been a professional football player for 13 years, a five-time Pro-Bowler, a two-time Super Bowl champ, a Dallas Cowboy. He can almost hear the voices of those who would accuse him of all manner of betrayal. Wasn't he supposed to be a role model? Someone who needed to send the right message to kids--a message in lockstep with the hard-line anti-drug stance of the NFL? But to sign on as the new president of Texas NORML, an organization dedicated to reforming marijuana laws, to join its national advisory board, well that just seemed a reckless way to kick off his retirement.

At 34, Mark Stepnoski could no longer keep his principles to himself. He had known hypocrisy in a league that generates huge revenue from alcohol and tobacco advertising, drugs that he believes are much more harmful than marijuana. He had been subjected to random drug testing for a recreational drug that in no way affected his performance on the field. He had sensed the futility of an unwinnable drug war whose main victims are marijuana users like himself, their lives ruined because of a law that he believes is as wasteful as it is unjust. Yet despite 20 years of personal use, he remained silent until retiring this season. "To come out when I was playing would have caused a lot of grief," Stepnoski says. "The media would have had a field day, and it would have generated a lot of negative publicity that the team certainly wouldn't have wanted. I didn't want it either."

By outing himself now, Stepnoski becomes one of the first NFL football players past or present to publicly advocate the decriminalization of marijuana and a powerful pitch man for drug-law reform. It's a common tactic, really--to enlist celebrities to sell your point of view, a tactic also employed by drug-war advocates in their zeal to win the hearts and minds of those in the murky middle.

Even as a player, Stepnoski was never one to seek celebrity, though he seemed to attract it by the cut of his hair, which was unconventionally long for the NFL. He was the center whose sweaty shoulder-length strands dangled beneath his helmet on game day. He was the 260-pound lineman who had to compensate for his smaller size by being quicker, stronger, more agile than the 350-pounders he was assigned to block. He was the publicity-shy ball player who chose to do his weight training during lunch and dodge the daily meet-and-greet with the media. "Every sports interview is just like every other sports interview--mindless questions, clichéd responses," he says. "If I had a nickel for every time some reporter asked me about my hair."

Stepnoski says he was all about the game; of course, the $14 million, five-year contract he signed with the Cowboys in 1999 just made the game that much more enjoyable. But playing ball was all he ever wanted to do, and he wanted to do it better than anyone else. His father played in high school, his brother in college, and he took to it naturally by age 9, playing throughout his school days in Erie, Pennsylvania. At the University of Pittsburgh, he played guard, making several All-America teams and attracting the attention of the Dallas Cowboys, which drafted him in the third round in 1989, a few months after Jimmy Johnson became head coach.

Starting at center by the end of his rookie season, his play took on an intensity, a seriousness of purpose, that put everything else in his life on hold. "I knew the average NFL career is four to five years," he says. "I pushed everything else out of my mind but football. You never knew when it was going to end." He delayed marriage and kids and says he shunned the kind of off-field carousing for which the Cowboys had become notorious. "I was serious about the game, so I didn't want to do anything to detract from my performance on Sunday."

That didn't stop him from lighting up the occasional post-game reefer, or smoking a joint to alleviate the pain from his banged-up right knee and the six surgeries he underwent to keep it functioning. "From my own personal experience, it seemed inherently less harmful than alcohol," he says. "When you are playing football in 105 degrees, and you drink a couple of six-packs, you can't go out the next day and perform. That's just not the case with marijuana."

The league mandated that each player submit to one random drug test annually, which could be administered any time between minicamp in April and training camp in mid-August. By abstaining for four to six weeks before minicamp, he passed every drug test he took. "It's all about responsible use," he says. "I could quit anytime. There was no withdrawal. No nothing."

Drug warriors would disagree, particularly the Office of National Drug Control Policy, whose recent anti-marijuana media blitz warns parents: "And don't be fooled by popular beliefs. Kids can get hooked on pot. Research shows that marijuana use can lead to addiction."

It's these kinds of ads, coached in qualifying words like "can" and "could," that cause drug-law reformers to brand them as propaganda, condemning their science as fuzzy, lacking peer review or replication. "Smoked marijuana is not harmless, but it is no more addictive than, say, coffee or tea," says Dr. Alan Robison, a former chairman of the department of pharmacology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston. "Young people know they are not being told the truth," Stepnoski adds, "which is exactly what erodes their trust in authority."

Stepnoski says he made it his business to educate himself on these issues, subscribing to High Times magazine and occasionally contributing financially to NORML. Risking exposure, he became a lifetime member by donating $2,000 to the organization in 1998. He envisioned becoming more of an activist, particularly as his career began to wane. Returning to the Cowboys from the Oilers in 1999, the game just wasn't the same for him. His closest teammates had either retired, been traded or both. The Cowboys were playing poorly, posting two losing seasons (2000, 2001), and football just didn't seem as much fun anymore.

The call from Jerry Jones came as no surprise last February. The Cowboys would be releasing him; he was too expensive, they had to think salary cap. Stepnoski's agent said there was some interest from the Washington Redskins, but after 13 years, he knew he was done. "I felt fine walking away from the game, because I reached the point where I was convinced I just couldn't physically stand the rigors of an entire season."

A year earlier, Rick Day, then the executive director of Texas NORML, had written him a letter, hoping to enlist his support: "I expect you may be in the process of re-evaluating your life...so let me suggest a new challenge: the regulation of marijuana for adults in Texas. Think of it as the culmination of a career as a Texas icon."

Once matters with Jones were settled, he phoned Day and told him he was ready to do what he could: help lobby the upcoming Texas Legislature to decriminalize marijuana; join NORML's national advisory board of celebrities; even take over as the new president of Texas NORML since Day would be moving to Atlanta.

"To change a law, you have to change people's minds about the law," says Allen St. Pierre, national executive director of the NORML Foundation. "Celebrities and athletes are the best placed to change the minds of others. Marketers know it. Politicians know it. Not surprisingly, drug-law reformers know it, too."

Stepnoski hopes to debunk what he calls the "faulty assumption" that pot causes amotivational syndrome, which is characterized by a decrease in drive, ambition and productivity (read: burned-out stoner). "Having someone like me on NORML's national board can dispel this myth. You can't play football in the NFL at my level for 13 years with amotivational syndrome."

The Cowboys refused to comment on Stepnoski's foray into pot politics, and when former teammate Darren Woodson heard about it, he acted surprised. "Whoa, no comment. I don't want to say anything about that. I got kids."

Stepnoski, however, believes he is acting as a positive role model by bringing truth to whoever is willing to hear it. He believes he is modeling "responsible use" by agitating for laws that allow only adults to possess marijuana in the privacy of their own homes, through a regulatory scheme similar to beer or tobacco, which does not waste valuable police resources and frees the nonviolent pot smoker from the risk of prison.

"Football is part of the American culture, but it is still a game," he says. "What I am dealing with now is not a game. We are talking about people's lives."

NBA Star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Arrested for Pot

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is clearly one of the greats of basketball. Jabbar, 53, is the NBA's career scoring leader with 38,387 points in the regular season and 44,149 total, including playoffs. The 7-foot-2 center, known for his all-but-unstoppable hook shot, led the UCLA Bruins to three consecutive NCAA championships before joining the NBA. In a career spanning 20 seasons, Abdul-Jabbar played in 19 All-Star games and won six MVP awards.

The basketball great has said he uses marijuana to alleviate the migraine headaches that have bothered him for years. ``I use it to control the nausea which comes with the headaches,'' he said during a book signing last year and upon the time of his arrest for carrying a small amount of the drug through Toronto.

Source:, July 18, 2000, Associated Press

Four Olympic medals for pot smoker

Olympics-Swimming-Hall nearly missed Sydney Games

By Phil Whitten

SYDNEY, Sept 23 2000 (Reuters) - American Gary Hall, who won two gold medals in the Olympic pool this week, said he nearly missed the Games after refusing to pay a fine for appealing against a ban for marijuana use.

Hall appealed against a three-month suspension imposed in 1998 by world swimming's governing body FINA after he tested positive for marijuana but the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) upheld the ban last year.

Hall said FINA had said it was a second offence but he considered it should have been considered a first infraction as the first time he tested positive -- at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics -- marijuana was not on the list of prohibited substances.

Hall, who shared victory with fellow American Anthony Ervin in Friday's 50 metres freestyle final and anchored the US 4x100 medley relay to victory in world record time on Saturday, said he had received a faxed message from FINA on August 22 demanding he pay a fine of 10,000 Swiss francs, plus interest, by August 24.

The deadline for federations to submit their Olympic entries was August 25.

Hall refused to pay, saying: ``If that means I won't compete in Sydney, then so be it. It's a matter of principle.''

However, the US swimming federation decided to pay the fine on condition that Hall agree to conduct several swimming clinics for American youngsters without pay, which the swimmer accepted.

Hall won four medals in the Homebush Bay pool -- gold in the 50 freestyle and medley relay, silver in the 4x100 freestyle relay and bronze in the 100 metres freestyle.

09-23-00. Copyright Reuters Limited.

South African cricket heroes busted for dagga!

By Jermaine Craig and Xolisa Vapi, June 2001

South African cricket has been hit by a new scandal after five members of the team touring the West Indies, as well as the team's physiotherapist, were caught smoking dagga.

Herschelle Gibbs, Andre Nel, Paul Adams, Roger Telemachus, Justin Kemp and physio Craig Smith were each fined R10 000 by an on-tour misconduct committee. According to United Cricket Board (UCB) president Percy Sonn, they were given a "moerse" (very serious) warning after they admitted smoking dagga on April 10 as part of the celebrations for winning the Test series after the fourth Test in Antigua.

UCB chief executive Gerald Majola, who is in the West Indies, has called for an urgent meeting with the team to discuss the matter. Majola said the men should have known they were ambassadors for their country and were in the public eye.

… He said he had met with team management and was due to meet the team on Friday night. He said the culprits could possibly face further action, because the matter would be referred to the UCB executive committee when it meets on Thursday.

He said the incident happened after a victory. The men were out celebrating and, "like normal human beings", were "trying new things".

A UCB statement said the accused had all admitted their guilt and that the misconduct committee (made up of team management and senior players) accepted that this was a one-off incident.

The accused had all expressed remorse, apologised and gave an assurance that it would not happen again. Gibbs would face the music on his return

"I was very disturbed when I received the report, particularly because one of our management staff was involved. But we have seen the sentence handed down by the misconduct committee and concur with it," Sonn said.

Questions have to be asked about why the incident, which occurred more than a month ago, has only now been made public, after the misconduct committee reported it only on Friday.

… Ironically, all five players involved in the dagga incident could play in the sixth one-day international against the West Indies in Trinidad on Saturday. Sharks rugby team doctor Craig Roberts explained that marijuana is not a stimulant, but rather suppresses the central nervous system.

"But it would really depend on how much the players had and the manner in which it was taken - whether they smoked it or ate it," he added. "What it does is stimulate some of the senses while inhibiting others."

Marijuana can stay in the system for up to six weeks, Roberts explained.

After the 1994/1995 New Zealand tour to South Africa, three young and upcoming New Zealand cricketers - Stephen Fleming, Matthew Hart and Dion Nash - were suspended for three games for celebrating with dope .